Episode 3: Three convicts, twenty dollars, and a newspaper

Started in 1887 by three well-known convicts, The Prison Mirror is often considered the best prison newspaper in the United States. But it is just one of many. In the 1980s, Robert Taliaferro was a writer and editor for The Mirror, as it was called in those days. Shannon Ross is a writer who started The Community in 2014 when he was in prison. The newsletter, which he still edits today, reaches half of Wisconsin's prison population. With hosts Adam Carr and Dasha Kelly Hamilton, Robert and Shannon come together to talk shop. We hear from them about why their work centers human-interest stories from people who are incarcerated and what we can learn from those who have an inside perspective.

Listen Now

In any listening app or here on this page.

Episode Extras

The Prison Mirror

“The introduction of the prison press into the great penal institutions of our land is the first important step taken toward solving the great problem of true prison reform.” — Lew P. Schoonmaker from the 1887 inaugural issue of The Prison Mirror.

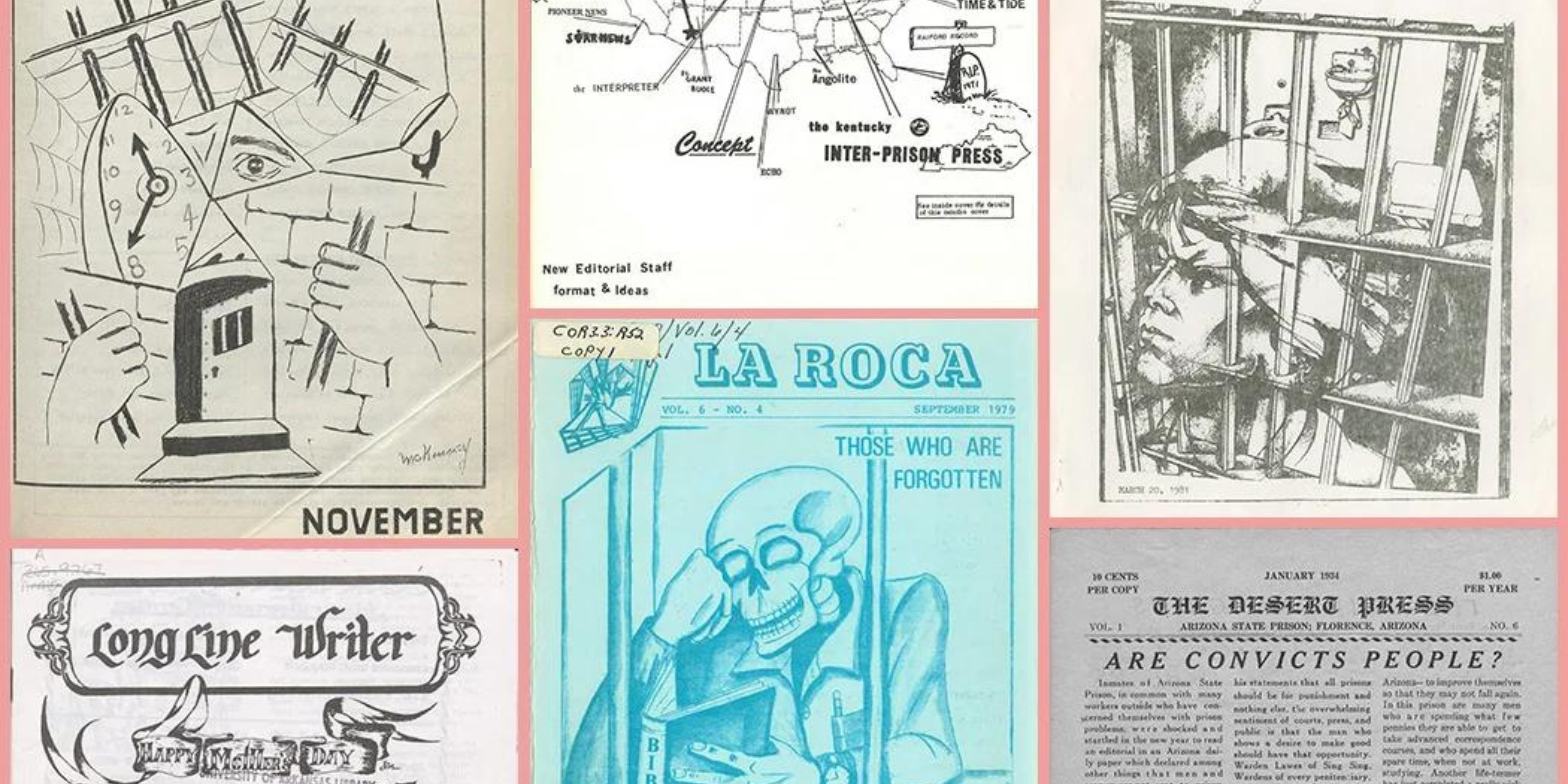

The digital image of that first paper (above) is part of the American Prison Newspaper Collection. The collection was founded in 2020 to professionally archive the over 700 prison newspapers that depict and report on life within the walls of prisons. Some publications, like The Prison Mirror, are produced with the permission of institutional authorities, while others are produced underground.

Robert Taliaferro speaks about his experiences writing and editing The Prison Mirror in episode 3 of Human Powered podcast. Throughout its long publication history, it has been recognized by other newspapers for the quality of its writing and has won awards for the best prison newspaper in the United States several times. You can read more about the history from the Minnesota Historical Society.

Meet Robert

“I always wanted to get an education, and I think education in prison is a necessity. Do we want people to come out of prison the same as they came in, or do we want them to come out and get jobs, pay taxes and be responsible citizens?” - Robert Taliaferro

After serving 38 years in prison, Robert returned home with more than 175 college credits and a resume that included editing an award-winning prison newspaper, The Prison Mirror. He now spends his time working for foundations, state governments and universities. He is an advocate for prison education programs like Odyssey Beyond Bars, one of the programs he participated in at Oakhill Correctional Facility.

About his work at The Prison Mirror, Robert said : [I]t was my mission to expand prison journalism beyond the walls to create more than just a prison rag for the 1,400 men who resided at [Minnesota Correctional Facility] Stillwater, but to create a window to our world for the community at large.

Read an article by Robert written for the Prison Journalism Project.

Meet Shannon

“Before I could actually get to a point where I was a good writer, if I even dare say that about myself, I had to become aware of what it meant to be a human being. You know, what it meant to be a flawed individual, which we all are, who’s done something terrible. And so grappling with what it means to exist in this world.” – Shannon Ross

The Community is a newsletter that Shannon started when he was inside. It started in print, but now reaches half of Wisconsin’s prison population through email, and even more people on the outside. Something like 30,000 people read each one.

In episode 3 of Human Powered, he talks about his reasons for starting The Community and his continuing work to change the narrative about how the general public understands the prison system and people impacted by it. The "Correcting the Narrative Campaign" uses story-telling and live events to promote acceptance of people with criminal records as neighbors, employees, and potential family.

You can learn more about his work and subscribe to receive The Community newsletter here.

Independent Journalism

The Prison Journalism Project is a national network of prison journalists who bring transparency to the world of mass incarceration from the inside. As of March 2023, this includes over 600 writers in 195 prisons in 35 states.

PJP also trains incarcerated writers to be journalists and publishes their stories. In 2021, they launched PJP J-School, a correspondence-based journalism course tailored for prison writers. The first cohort had 15 students from around the country. Additionally, a partnership with the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) has established the first national chapter of incarcerated journalists.

Their Prison Newspaper Project was launched to facilitate connections between publications and with the broader general audience, including educators and researchers. On their website you’ll find:

- - A prison newspaper directory with contact information.

- - A selection of republished stories "From Prison Newspapers" to increase accessibility because many prison publications do not have an online presence.

Voices from the Inside

People inside U.S. prisons have been running their own newsrooms since 1800. The Prison Journalism Project (PJP) reports that by their count in February of 2023, there were 24 operational, prisoner-run news publications at work across 12 states. Collectively known as the prison press, the efforts of incarcerated writers and editors have taken many forms over the years, from short, mimeographed newsletters to thick, glossy magazines. The first study on prison newspapers was conducted in 1935 and reported that nearly half of U.S. prisons produced their own publications. The numbers hit an all-time high in 1959, with 250 prison papers appearing regularly nationwide. But by 1967, that number was at a low, with just six actively publishing prison newspapers.

In 2020, the American Prison Newspaper Collection was started to bring together hundreds of these periodicals from across the country into one collection. It represents penal institutions of all kinds, with special attention paid to women-only institutions. It is an open-source resource curated by an editorial board of library leaders and hosted by the digital library JSTOR.

They explain on their website: With the United States incarcerating more individuals than any other nation–almost over 2 million as of 2023–these publications represent a vast dimension of media history. These publications depict and report on all manner of life within the walls of prisons, from the quotidian to the upsetting. Incarcerated journalists walk a tightrope between oversight by the administration – even censorship – and seeking to report accurately on their experiences inside. Some publications were produced with the sanction of institutional authorities; others were produced underground.

Reflections

In episode 3, we hear about two prisoner-run news publications. Here are a few questions to get you thinking, whether you've listened yet or not.

One example of a story from The Mirror is about someone who won a bonsai contest. Adam says that for people reading this kind of article, "their humanity is reflected back at them." What does that mean to you?

For Shannon and Robert, it is important to center the humanity of people in their stories. Shannon says, "when the plant's up, nobody wants to look at the roots in the soil. Nobody wants to look at, you know, what happened before you saw the blossoming." What does this mean to you?

Shannon and Robert both talk about 'correcting the narrative." What does that mean to you?

Going Deeper

Kamika Patel was a summer intern for Wisconsin Humanities while also participating in a study abroad program in Norway through the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She brought a global perspective to her work with Wisconsin Humanities and drew on her past experience working for another nonprofit focused on racial equity. Kamika wrote about her own background and her current thinking about how to break through stereotypes and biases.

You can read Kamika's reflections here.

Episode Guests

Shannon

Shannon Ross is the founder and Executive Director of The Community and the Correcting the Narrative Campaign, which uses story-telling to promote acceptance of people with criminal records. Shannon was born and raised on Milwaukee’s north side, where he received a 17-year prison sentence when he was 19 years old. Over the course of his incarceration, he acquired his bachelor’s degree, created and ran a mental health program in the prison for 2 years that still exists, and published his own and others' writing. Since his release in 2020, he helped to found Paradigm Shyft, is an Education Trust fellow, a Marquette University EPP fellow, and a graduate of the Masters in Sustainable Peacebuilding program at the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee.

Robert

Robert Taliaferro is a working journalist, graphic artist, and community activist currently living in Minnesota, after serving over 38 years of confinement. He edited The Prison Mirror newspaper at the Minnesota Correctional Institution at Stillwater from 1985-1989. His work is published in News and Letters Committees and he is the author of Always Color Outside the Lines: Freedom for the Artist Within (2018). He recently graduated from Metro State University in St Paul, MN where he was the Outstanding Student Award recipient for the College of Individualized Studies and also gave the Commencement address. He is beginning a graduate degree program in the fall and will be studying Urban Developmental Initiatives and Adult Education.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Get the latest information about our podcasts and other news by subscribing to our newsletter.

Episode Credits

Hosts: Adam Carr and Dasha Kelly Hamilton

Senior Producer: Craig Eley

Producers: Jen Rubin and Jade Iseri-Ramos

Executive Producers: Dena Wortzel

Creative Producer: Jessica Becker

Photography: Jessica Becker, Nicole Acosta